Last week we highlighted the

utility of shapely fragments. However, as the latest review of fragment-to-lead

success stories again shows, starting with a “flat” fragment does not condemn

a lead to flatland. This is illustrated in a recent J. Med. Chem. publication

by Adam Charnley and colleagues at GlaxoSmithKline.

The researchers were interested

in receptor interacting protein 2 kinase (RIP2), which is implicated in various

inflammatory diseases. A fluorescence polarization screen of 1000 fragments at 400

µM yielded 49 hits with inhibition constants ranging from 5-500 µM. Thirty of

these confirmed in a thermal shift assay, and 20 were characterized

crystallographically bound to the enzyme. Hit-to-lead chemistry was pursued for

five series; the most successful started with compound 1a.

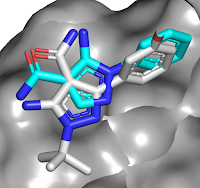

The crystal structure revealed

that the carboxamide of compound 1a makes interactions with the hinge region of

the kinase, with the phenyl group in the back pocket. A search of related

molecules available in-house led to compound 2a, with a satisfying boost in

potency. Interestingly, the crystal structure of this molecule bound to RIP2

revealed that the binding mode of the pyrazole moiety had flipped to keep the

phenyl ring in the back pocket (compound

1a in cyan, 2a in gray). Enlarging the phenyl group to better fill the pocket

led to compound 2k.

The crystal structure revealed

that the carboxamide of compound 1a makes interactions with the hinge region of

the kinase, with the phenyl group in the back pocket. A search of related

molecules available in-house led to compound 2a, with a satisfying boost in

potency. Interestingly, the crystal structure of this molecule bound to RIP2

revealed that the binding mode of the pyrazole moiety had flipped to keep the

phenyl ring in the back pocket (compound

1a in cyan, 2a in gray). Enlarging the phenyl group to better fill the pocket

led to compound 2k.

This molecule had relatively poor

selectivity against several other kinases, but introducing a ring as in

compound 8 improved the situation. Crystallography suggested that installing a

bridged ring would pick up further interactions with the protein, and although

the resulting molecule did not have better affinity, selectivity improved.

Finally, a hydroxyl group was introduced (compound 11) to try to pick up interactions

with a non-conserved serine residue. This addition did not improve biochemical

activity, and in fact a crystal structure revealed that the hydroxyl group was

pointing towards solvent, but the activity in human whole blood improved.

Importantly, compound 11 was remarkably selective for RIP2: just 1 of 366 other

kinases tested at 1 µM showed >70% inhibition.

This is a lovely fragment-to-lead

success story that reiterates several important lessons. First, a generic (in

this case commercial) and nonselective fragment can lead to novel, selective

series. Second, as has been seen multiple times, fragment binding modes can

flip unexpectedly, especially during early optimization. Finally, despite the relative

flatness of fragment 1a (Fsp3 = 0, though the two aromatic rings are

slightly twisted), it could be optimized to a more shapely lead, and the increased complexity is likely responsible for the impressive selectivity. Left unreported is

the stability and pharmacokinetics of compound 11: the hydroxyl and all those sp3-hybridized

carbons are likely metabolic hotspots. As is so often the case in lead discovery,

what solves one problem can too often create another.

No comments:

Post a Comment